By Hanah Stuart

Composer, violinist, and Pittsburgh native, Tommy Dougherty, was commissioned to write a piece for the Laurel Arts Exhibit in Somerset, PA, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of 9/11. The piece, titled “Blue Steel Cranes” and scored for Oboe, Viola, and Harp, received its premiere performance at Laurel Arts’ “Reflections of the Human Spirit” exhibit in September.

How are you approached for commissions?

This piece wasn’t a normal commission situation where I was approached by an ensemble to write a piece, but rather a competition for the opportunity to be commissioned. For this competition, the Johnstown Symphony Orchestra welcomed composers to submit works in addition to writing a cover letter explaining their ties to the Western Pennsylvania region. This grabbed my attention considering both my family’s ties to the region and how supportive it was to my own musical upbringing. My grandfather was the cousin of the former mayor of Pittsburgh and worked in the Steelers and Pirates stadiums for 62 years. My dad’s first job out of college was working in a steel mill, and my mom was a music director for the Diocese of Pittsburgh for over thirty years. Growing up, I studied with musicians in the Pittsburgh Symphony and composers at Carnegie Mellon University. Given my connections, it was an honor to be chosen to represent the region.

When you won, what happened?

This past June, JSO music director James Blachly notified me that I had been selected and invited me out to Johnstown and Somerset for the Symphony’s season announcement, as well as to visit the Flight 93 memorial in Shanksville and Laurel Arts in Somerset. Laurel Arts co-commissioned the work with the JSO, and it became clear that I would be writing for their exhibits honoring the 20th anniversary of 9/11. The work was to be written for a trio of JSO musicians (oboe, viola, and harp) and would be performed at Laurel Arts, surrounded by the exhibits. I would have about a month and a half to write a three movement, 10-12 minute work.

Can you tell us about Laurel Arts and what inspired you for the work?

Laurel Arts is the only rural arts center in the entire state of Pennsylvania which really blew my mind. Before I knew anything about Laurel Arts and heard “Arts Center,” I imagined a brand-new Frank Gehry glass building. However, the building itself happens to be the home of the founder of Somerset, built in 1832. His descendants bequeathed the house to Laurel Arts some time ago. It makes for a big house and a homey vibe with very tall ceilings and beautiful gallery space. Laurel Arts serves the community in countless ways, offering classes and creative spaces to local school kids and adults alike.

Each room on the ground floor had a different exhibit. I composed three movements to represent each of these three exhibits. Upon visiting, I was inspired by the clear vision executive director Jaclyn McCusker had for this collaboration, and it encouraged me to know that my work was focusing on the many aspects that make Somerset a unique, resilient place, as opposed to purely focusing on the tragic and horrific events of 9/11.

Can you describe the three exhibits from Laurel Arts that your piece is centered on?

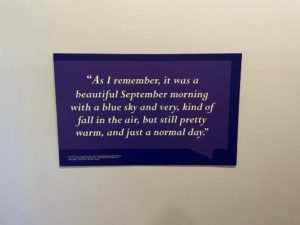

The first room was focused on the bucolic nature of Somerset, Pennsylvania, particularly the rolling hills and the clear blue sky of that morning. In speaking with locals about the morning of 9/11/2001, it’s something they all recall, how clear and blue the sky was, and you can see in quotes at the Flight 93 Memorial; ‘the limitless blue sky’. It’s also how I arrived at the title for the movement, “Blue.” The room was collaborative in that a local photographer was featured with photos of the region. They wanted my piece to be reflective of the natural quality of the area and setting a scene of what that day could have been. So in that sense, the first movement was the easiest to compose. Composers inspired by nature… it’s a thing!

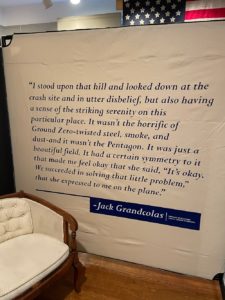

The second room was more focused on the aftermath of the crash and the response, which for me was the most difficult to write. Jaclyn and I agreed that musically this should be the most distant of the three movements, as there would be media clips being played throughout the exhibit and debris from the crash site present. Considering the emotional weight of an exhibit like this, I went with a less is more approach. In recalling my own experience on 9/11/2001, I remember the deafening stunned silence and how musicless the day felt. It was difficult for me to think I could contribute much musically in this situation, so I decided the movement would only be solo viola with a practice mute, distant, quiet, and comprised of fragmented melodies and sounds. “Steel” became the title of the second movement, considering the debris, the steely resolve of the community, and the material of the practice mute.

The third room featured hundreds of paper origami cranes (third movement title: “Cranes”) that are suspended from the ceiling. This exhibit displayed the hope and unity between the families of the victims and the community of Somerset that has developed over the years. The cranes are symbolic on two levels; one being a remembrance of Sadako Sasaki, the girl most famous for making paper cranes and a victim of the Hiroshima bombing, whose cranes became a symbol of peace and healing. The cranes also serve symbolic importance to one of the youngest passengers of the flight, Toshiya Kuge, who was a Japanese exchange student. His mother comes to Somerset every year and lays a paper crane at his grave.

Musically, the beginning of the movement is more active and rhythmically driving, representing the paper cranes taking flight. Harmonically, the entire movement is based off of the pitches from the Tower of Voices, a 93 ft tall tower of wind chimes at the Flight 93 memorial. It was a serendipitous discovery to find that when you lay out those 6 pitches across the range of the range of the harp, it uses exactly 40 strings, which was the number of passengers on the flight. Symbolically the harp functions as the tower does in that the voices that had been silenced on 9/11 have a space to sound.

The second half of the piece is slower and has a much freer feel to it. I rhythmically encoded the names of the passengers into the harp part, still using the same pitches from the tower. When familiarizing myself with the stories of the passengers in the early stages of writing the piece, I found myself watching past ceremonies where they say the names of the passengers and then ring a bell. There was something about the rhythm of the ceremony that felt like an appropriate way to honor the victims and end the piece.

Can you tell us a bit about the performance of the piece itself?

Initially each movement was going to be performed with the corresponding exhibit it was written for. That became complicated in that the exhibits were packed and logistically moving performers and audience (and a harp!) through the house wasn’t going to be feasible. So plan B was to have the piece performed in the first exhibit, which was the largest and most spacious. But upon further thought, I looked around the entire space for a different idea. It’s a big property and in the back there’s a huge yard and a gazebo and stage. The previous night I was at the vigil at the memorial where musicians from the Johnstown Orchestra played Mahler’s “Adagietto”, Barber’s “Adagio for Strings”, and George Lewis’s “Lyric for Strings” outside. The performance was very moving and all the families of the victims were present. The next day, I thought it would be better outside, not only from a COVID-19 standpoint, but also considering the first movement focuses on the nature of Somerset. There was only one disruptive gasoline tanker engine that revved by and distant cheers from a football field but I was all for it. It was a very John Cage experience. The next week, a recording was made of each movement to be put on loop in their respective exhibits.

We heard you also had something special made to wear for the event.

Yes! For the concert, I commissioned something to wear from my good friend and San Diego Symphony colleague, Nicole Sauder. We discovered a blue crane print and she made a beautiful shirt that I wore to the performance. I am all for art inspiring other art, and especially for “thinking outside of the suit” when it comes to composer concert dress!

Does this piece represent your usual style or did you tailor this differently than some of your other works?

Yes and no. On the one hand I’ve found it’s impossible to completely escape yourself artistically, even when you try! On the other, I would say that this piece went down a different path from the trajectory I feel like I’ve been on recently, which is exploring experimental string music. I would say because of all the factors that went into this piece, “Blue Steel Cranes” is different from most of my recent works, and I’ve grown to appreciate that about the piece!